Chokuretsu ROM Hacking Challenges Part 2 – Archive Archaeology

Last time, we talked about how I reverse-engineered the compression algorithm used in Suzumiya Haruhi no Chokuretsu. Today, we’ll be taking a look at the archives that contain the Chokuretsu files. Please note that while I’ll generally try to keep these blog posts separate, this one absolutely builds on concepts we discussed last time, so I highly recommend you read it first! Also, if you're returning from the last one, fair warning that this one's a bit longer and contains a lot more assembly!

Thanks to the proliferation of zip files, you’re likely already familiar with archives: they’re files that contain files, usually compressed versions to help save space on disk. Common archives include .zip, .rar, .7z, and .tar.gz files. Chokuretsu uses a custom archive format with the extension .bin. Since Shade is the developer of Chokuretsu, these files are referred to as “Shade bin archives” or just “bin archives.” Let’s get started by picking an archive to look at.

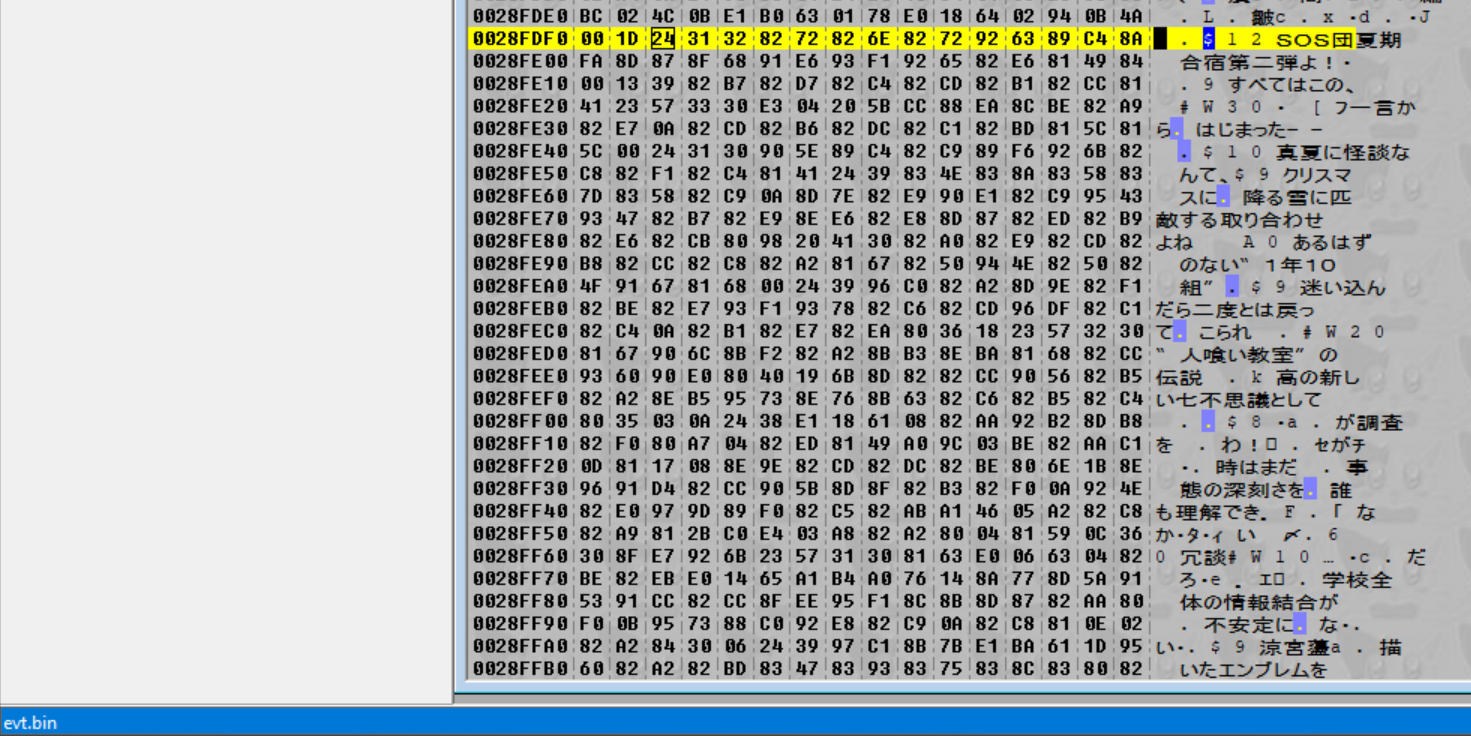

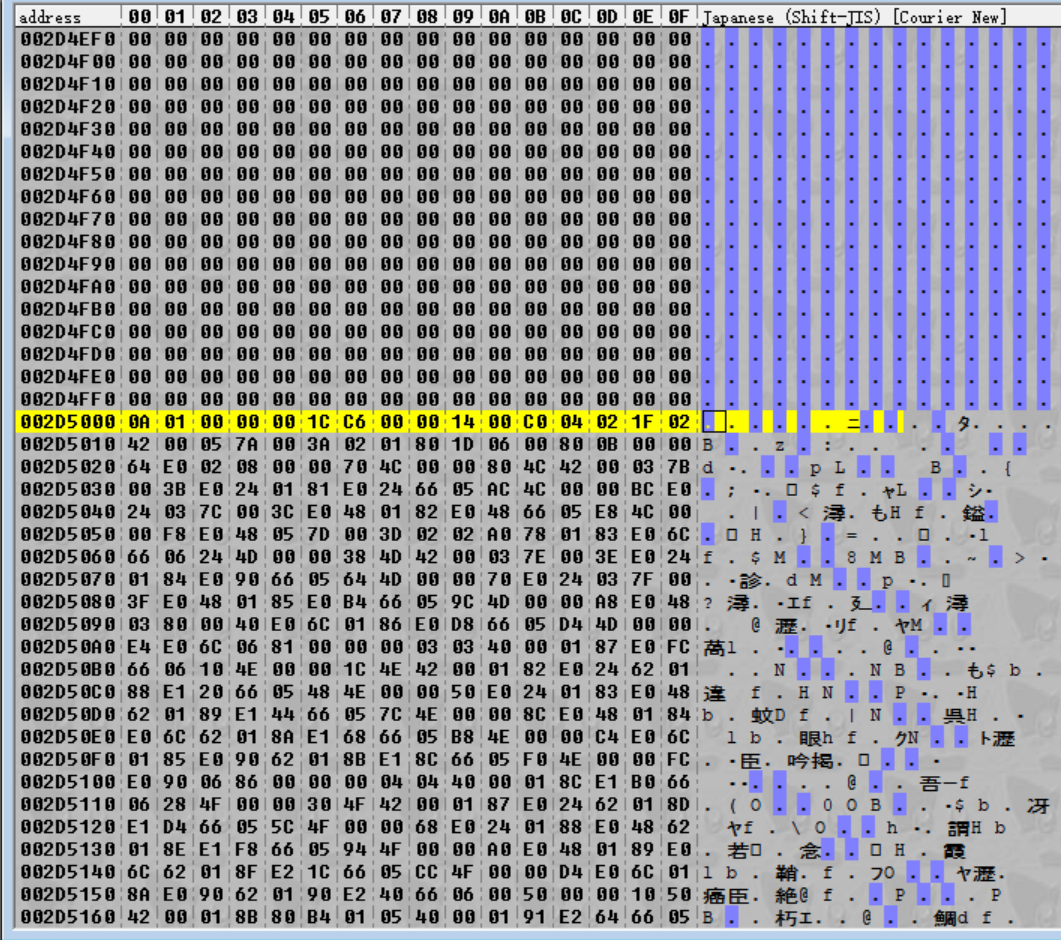

For convenience, let’s pick the archive that contains the file we were looking at last time. We can open the game up in CrystalTile2 and navigate to where we were looking last time…

And in the lower left corner it tells us that this data is contained in evt.bin (which is what we might have guessed, since it’s string data).

Examining evt.bin

Before we open it up in the hex editor, though, let’s talk a bit about what we’d expect to see in an archive (in order to confirm that evt.bin is in fact an archive). Here’s the attributes I’d put down:

- The number of files in the archive

- A list of files in the archive – this would be composed of filenames and offsets

- The file data for all the files

A quick explanation on that second bullet – filenames are self explanatory, but an offset is a way of talking about the location of data in a file. Briefly:

- An address is the absolute location of data in memory. When we set memory breakpoints in the debugger, we use addresses.

- An offset is the relative location of data in a file. When we have a single file open in the hex editor, we talk about offsets.

- A pointer is a value that points to an address or offset. A pointer to an address might look like an integer with the value 0x0220B4A8, while a pointer to an offset might be as simple as 0x3800. Addresses are used by the program when accessing memory, while offsets are used in files (since they can be loaded into arbitrary locations in memory), so it’s up to the program itself to convert those offsets into addresses.

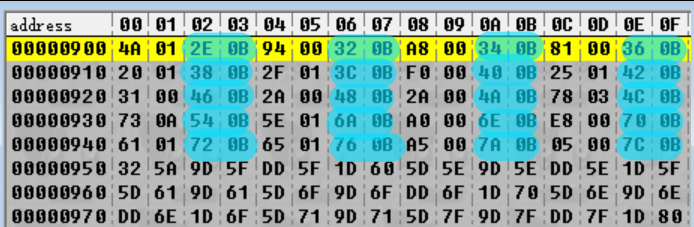

So with that out of the way, let’s crack open evt.bin. First thing we’ll do is scroll down a bit just to get a feel for the layout of this file…

Interesting! After we scroll past a large chunk of data, we end up in a field of zeros, followed by another large chunk of data and then another field of zeros and so on. What’s more, after we scroll past the first bit, each of the large chunks of data seems to start on a multiple of 0x800 (hard to get that sense from two images, but trust me, crack open the files and you’ll see the pattern). To me, this looks like the file data – and what’s more, each file is neatly spaced with padding in between.

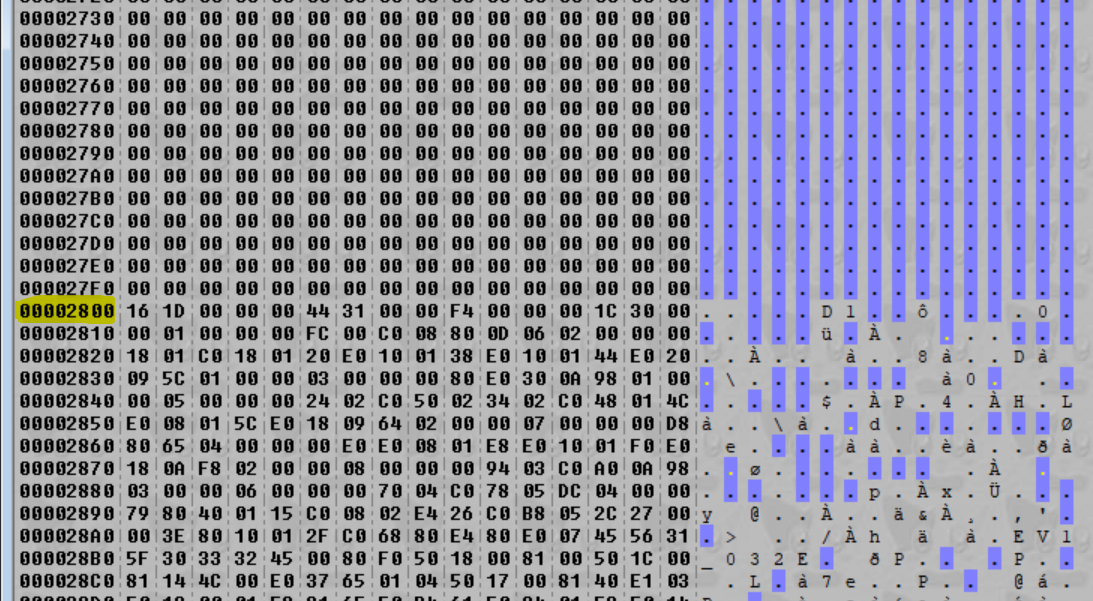

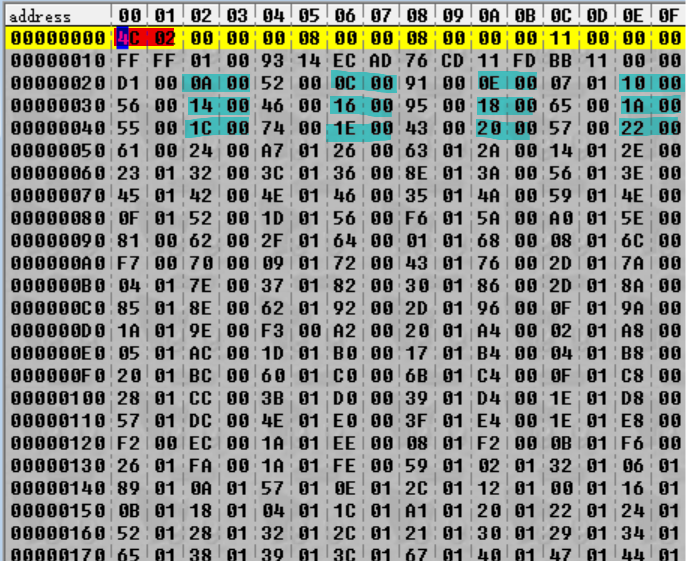

Let’s get back to the top of the file – again, a lot of numbers, but there are patterns here. But before we take a look at the numbers in cyan, a quick explanation on endianness. So far, we’ve mostly thought about things in terms of bytes, which can have values between 0 (0x00) and 255 (0xFF). But what about when we need to represent integers larger than that? When we need to do that, we use multibyte integers. The common types of these include:

| Number of Bytes | Formal Name | C# Name |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 16-bit integer | short (signed) or ushort (unsigned) |

| 4 | 32-bit integer | int (signed) or uint (unsigned) |

| 8 | 64-bit integer | long (signed) or ulong (unsigned) |

There are two possible ways to store a 16-bit integer, however. For example, take 512 (0x200). You could choose to store that with the most-significant byte first (i.e. 02 00) or with the least-significant byte first (i.e. 00 02). This decision is called endianness, where the former is “big-endian” and the latter is “little-endian.” Frequently, the decision is made simply to align with whatever the architecture uses; ARM is a little-endian architecture so these files are likely little-endian as well.

Going back to the cyan highlights in the image above, we can see that if we interpret the highlighted values as little-endian 16-bit integers, we have a sequence like:

0x000A, 0x000C, 0x000E, 0x0010, 0x0014, 0x0016, 0x0018, 0x001A, 0x001C, 0x001E, 0x0020, 0x0022 …

These integers are increasing as we continue along! In fact, they continue to increase for another 0x900 bytes, with the pattern terminating at the final integer 0x94E:

These definitely aren’t file offsets (the differences between them are too small – for example, a file between offsets 0xB2E and 0xB32 would only be four bytes long), but it’s possible they might map to file offsets somehow since they’re steadily increasing. That would suggest that maybe there is one of these values per file – so just how many are there? The values are two bytes long and spaced two bytes apart for a total of four bytes per iteration. The sequence begins at 0x20 and ends at 0x950. Therefore:

(0x950 - 0x20) / 0x04 = 0x24C

Oh! Look at that! 0x24C happens to be the very first number to appear in the file (highlighted in red). So we can guess that the first number is the number of files in the archive. (To double check this, we should check that the pattern is consistent for the other archives as well – which it is.)

What about the numbers next to the cyan highlights, though – the ones highlighted in green above? It’s hard to say right now as there’s no obvious pattern. However, we need some nomenclature here, so I’m going to be referring to the combination of the green and cyan highlights as magic integer, since they are obfuscated (magic) but do important stuff (also magic). The first magic integer spans from 0x20 to 0x23, which is why they’re “integers” – specifically, 32-bit integers.

Into the Thick of It, Reprise

The purpose of the previous section was to demonstrate how to a) identify that a file is an archive and b) use some basic pattern matching to begin reverse-engineering the archive. However, this archive is a little weird and obfuscated – while most archives might simply have a table at the top containing the filename and offset (location in the archive) for each file, this one clearly doesn’t have that. That information is somehow hidden. There are a variety of ways one could deal with this, but for me, the easiest option seemed to be diving back into the assembly again.

File Table Load

First, we should try to find the code where these archives are parsed. To do this, we’re going to do essentially the same process as we did last time – we’re going to do a memory search to find the archive header (the top of the file, before the files in the archive start) in memory, set a read breakpoint at that memory address, and see what code uses the archive header.

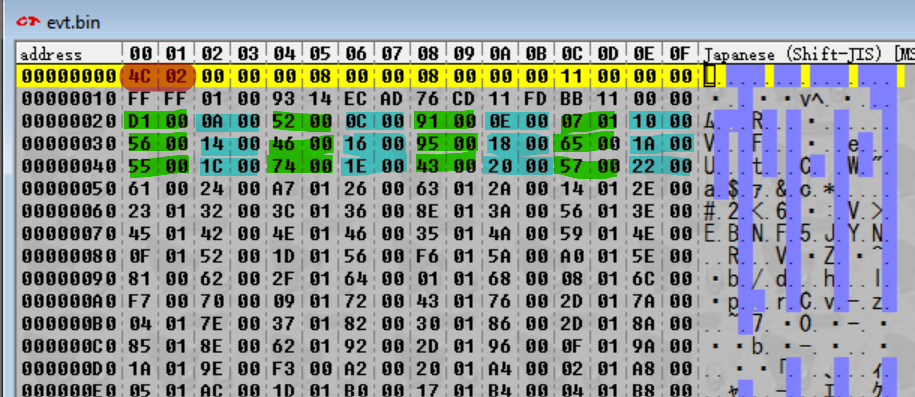

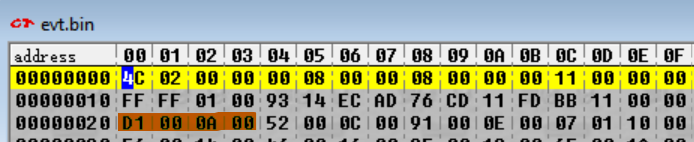

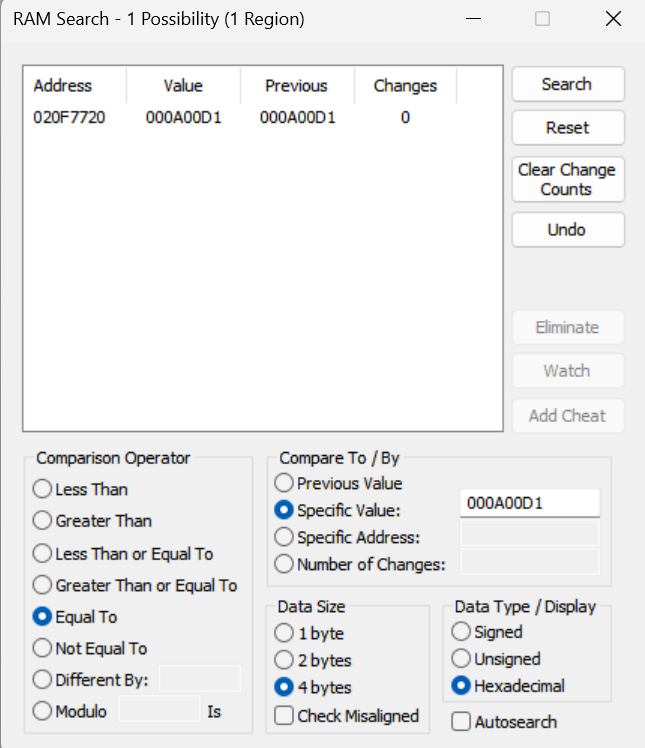

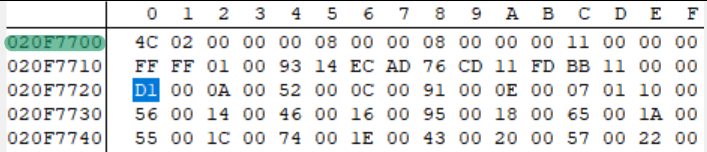

So, we go back to DeSmuME and search for the four bytes at offset 0x20 (remember, DeSmuME’s memory search expects you to enter the bytes in reverse order, so instead of D1 00 0A 00 we enter 00 0A 00 D1)...

And once again, we’ve found a single hit. So, let’s open up the memory viewer and head to 0x020F7720…

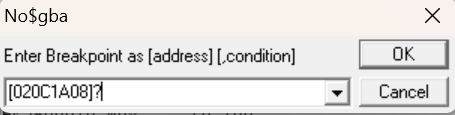

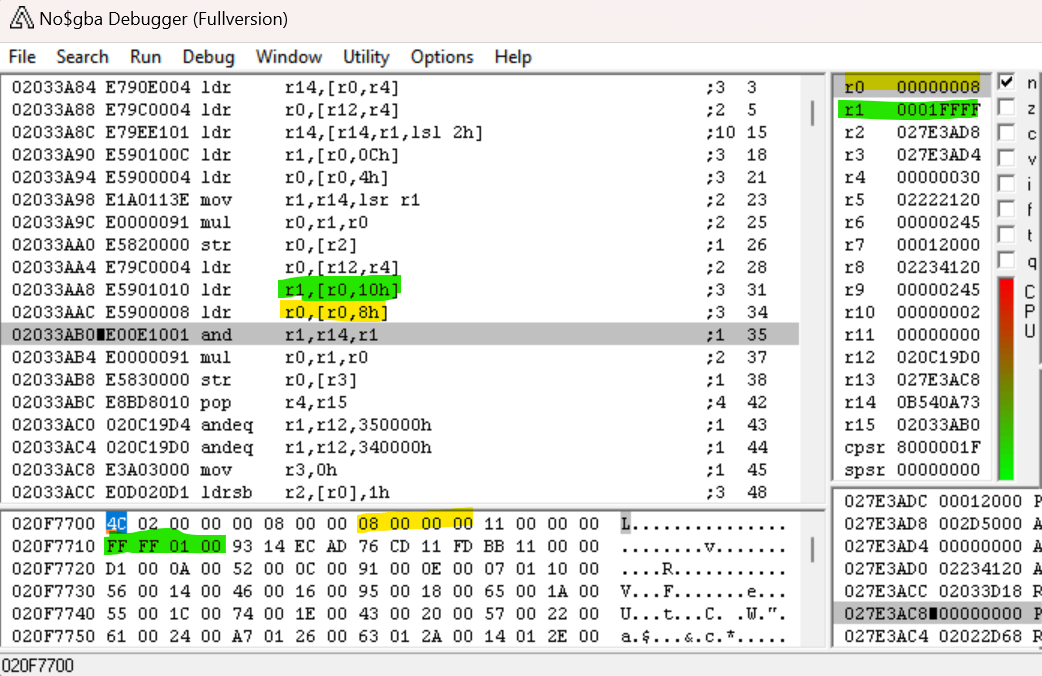

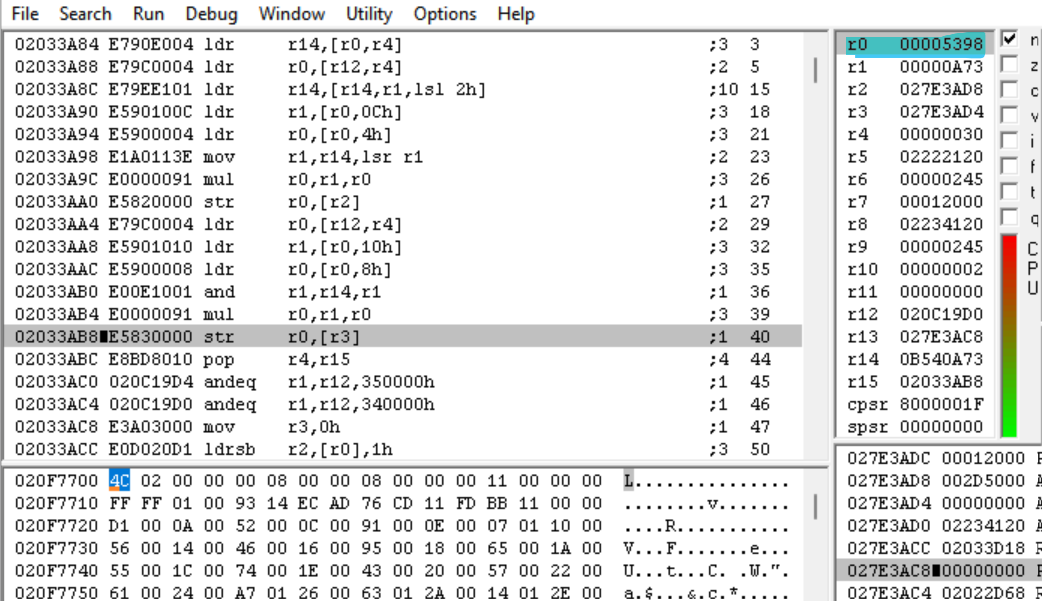

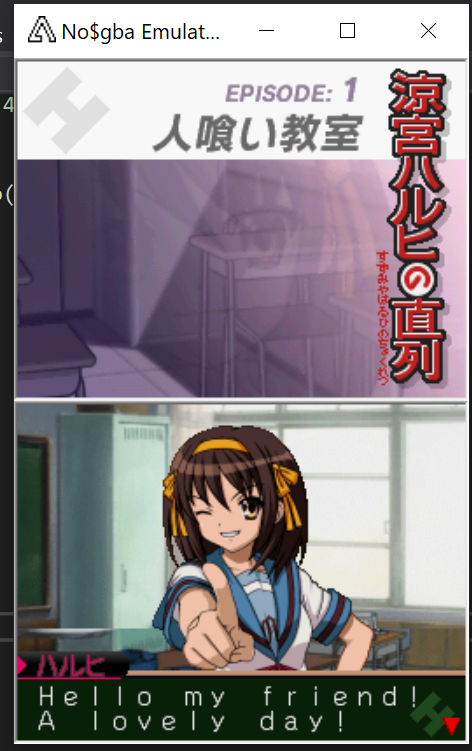

And it matches the evt.bin header exactly! This means that the evt.bin header is loaded into 0x020F7700. So now, we’ll load up the game in no$GBA (I was a little hard on no$ last time around, but its debugging tools are very convenient) and set a read breakpoint for 0x020F7700.

Nice, we hit our breakpoint as soon as the game is loaded. This means that the archive headers are loaded on boot. Let’s pull up this subroutine in IDA.

RAM:02033818 PUSH {R3-R9,LR}

RAM:0203381C LDR R2, =dword_20A9AB0

RAM:02033820 MOV R6, R0

RAM:02033824 LDR R1, [R2]

RAM:02033828 LDR R0, =aFiletblLoadSta ; "--- filetbl_load start <%d> ---\n"

RAM:0203382C ADD R1, R1, #0x3F ; '?'

RAM:02033830 BIC R3, R1, #0x3F

RAM:02033834 MOV R1, R6

RAM:02033838 STR R3, [R2]

RAM:0203383C BL dbg_print20228DC

Here’s something useful! That "--- filetbl_load start <%d> ---\n" string you see is text that’s hardcoded in the executable program (arm9.bin) itself.

=aFiletblLoadSta is a name IDA gives to the address that holds that string, so LDR R0, =aFiletblLoadSta is loading the address of that string into R0. In ARM assembly, R0 is used as the first parameter when calling another subroutine, so the BL (branch-link or “call this subroutine”) below uses it as a parameter. Because the string looks a lot like a debug string, we can guess that that function is a debug print function (something that would print text to the console for debugging purposes), which is why we’ve renamed the function here to dbg_print20228DC.

But more importantly, the fact that this debug string is being printed here tells us what this function’s name was in the original source code: filetbl_load(). From this, we can surmise that this function is designed to load the “file table” from the archive – i.e., it loads the header we were just looking at and that header is the list of files we thought it was! This trick (looking at debug or error strings to figure out what a function does) is something I frequently make use of – without even examining the disassembly in detail, we now have a pretty good idea of what this function does.

Loading the Magic Integer

After trying to analyze this routine the way we did the decompression routine, it turns out that this routine is a little bit more abstract. It references a bunch of memory addresses and other things that I don’t have any context for – so let’s get some context and watch what it’s doing in the debugger. After all, our goal here isn’t to necessarily reverse-engineer exactly what this routine is doing (unlike with the decompression routine), it’s to use this routine to understand the structure of the archive file.

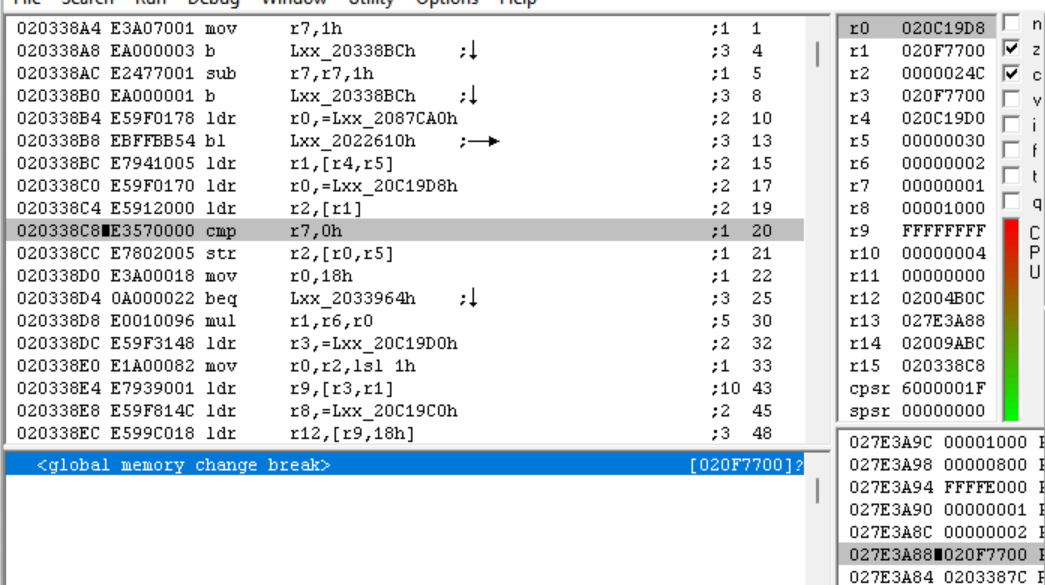

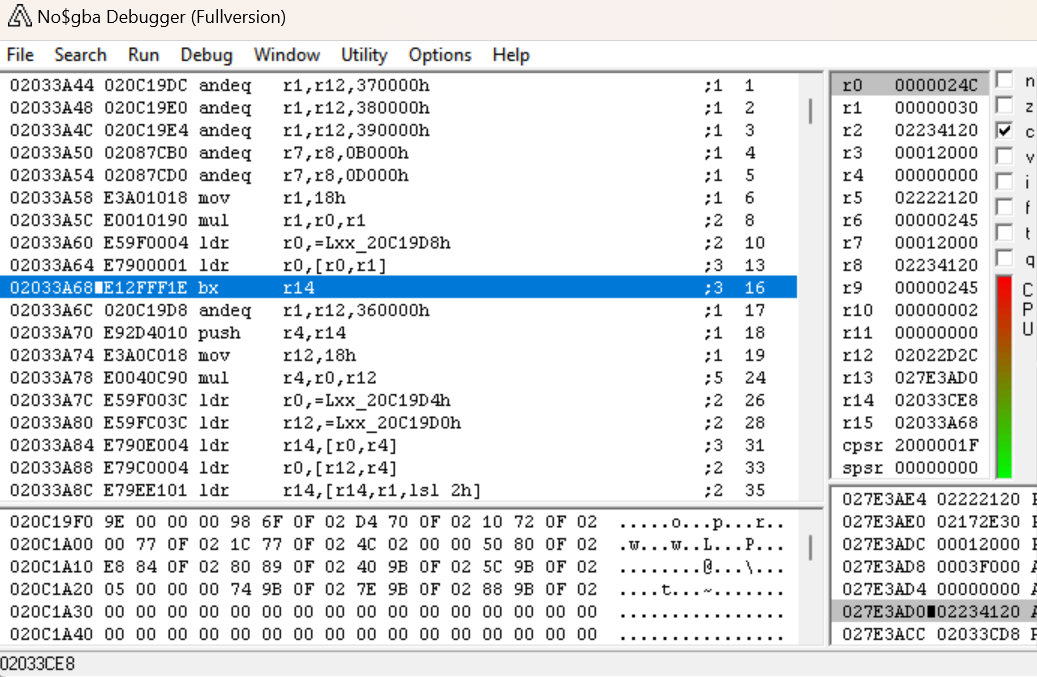

So back to no$GBA then. Stepping forward, we come to this STR instruction. STR R2,[R0, R5] should store the value of R2 (0x24C, what we’re suspecting is the number of files) in the memory location R0+R5.

After we step over that instruction, we can in fact see that 0x24C got stored in 0x20C1A08 as we would expect. So now, let’s set a read breakpoint for that address to see where it gets referenced.

We run the game…

And end up in this new subroutine. Navigating to this routine in IDA reveals that it’s very short.

RAM:02033A58 sub_2033A58

RAM:02033A58 MOV R1, #0x18

RAM:02033A5C MUL R1, R0, R1

RAM:02033A60 LDR R0, =dword_20C19D8

RAM:02033A64 LDR R0, [R0,R1]

RAM:02033A68 BX LR

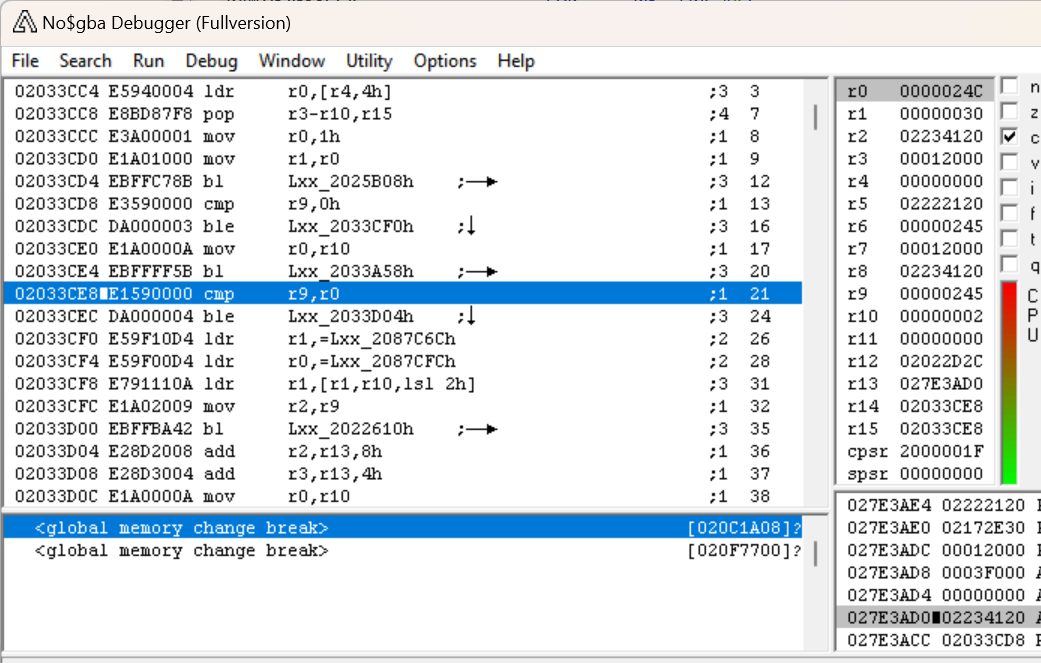

BX LR returns us to the subroutine that called this one, so given that we know the previous instruction is the one that loaded 0x24C into R0 (the register that is frequently used as a return value), we might be able to posit that the entire purpose of this subroutine is to load that value from memory. So, let’s rename this function to arc_getNumFiles and then step forward and see what called it.

Let’s pop open this section of this subroutine in IDA:

RAM:02033CCC loc_2033CCC

RAM:02033CCC MOV R0, #1

RAM:02033CD0 MOV R1, R0

RAM:02033CD4 BL sub_2025B08

RAM:02033CD8 CMP R9, #0

RAM:02033CDC BLE loc_2033CF0

RAM:02033CE0 MOV R0, R10

RAM:02033CE4 BL arc_getNumFiles

RAM:02033CE8 CMP R9, R0

RAM:02033CEC BLE loc_02033D04

RAM:02033CF0

RAM:02033CF0 loc_2033CF0

RAM:02033CF0 LDR R1, =sArchiveFileNames

RAM:02033CF4 LDR R0, =aFileIndexError ; "file index error : [%s],idx=%d\n"

RAM:02033CF8 LDR R1, [R1,R10,LSL#2]

RAM:02033CFC MOV R2, R9

RAM:02033D00 BL dbg_printError

So remember that coming out of arc_getNumFiles, R0 was set to (what we’re guessing is) the number of files. We can see that it gets compared to R9 immediately afterwards, and if it’s less than or equal to R9, we branch just past the end of the section I’ve shown. So let’s zero in on R9 – looking earlier up, we can see that R9 is also compared to 0, and if it’s less than or equal to zero we’re branching to loc_2033CF0. That’s the same location that we go to if R9 is greater than R0. If we examine that section, we can see another debug message – "file index error : [%s],idx=%d\n"! For those of you not familiar with C, this is a format string – the %s and %d indicate parameters to be inserted into the string. %s expects a string and %d expects a decimal number. We determined that the function that the BL is branching to is a “print debug error message” function by the fact that the string indicates an error is occurring, but this string gives us even more clues. So at a high level, this section is checking to see that R9 is greater than 0 and less than or equal to the number of files. If it’s not, then it throws an error.

When calling a function in a higher-level language, you specify parameters that get passed to the function. In ARM assembly, these parameters are passed by setting specific registers to specific values – the first parameter is set to R0, the second parameter is set to R1, etc. So, we know that this dbg_printError subroutine is going to print that format string. The string itself is loaded into R0, meaning that the first parameter is the string itself. The next parameter (corresponding to %s) should be loaded into R1, and the final parameter (corresponding to %d) should be loaded into R2.

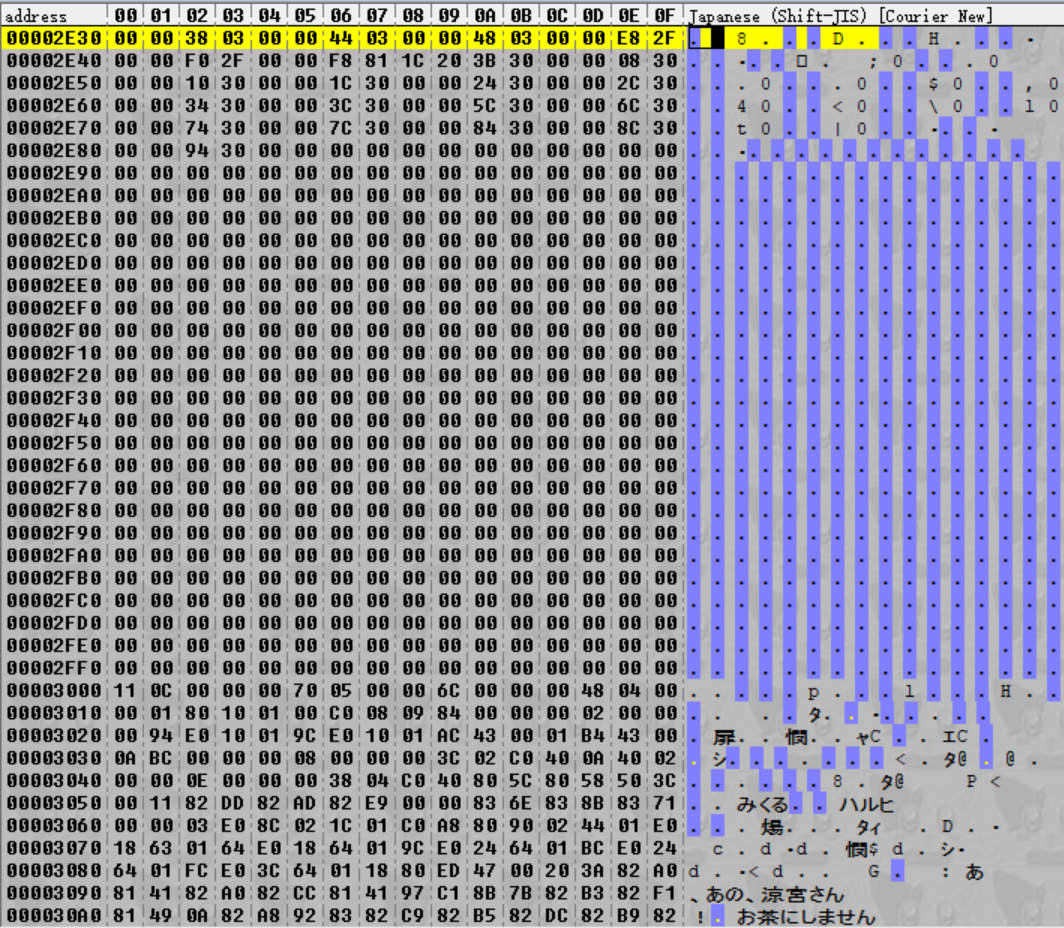

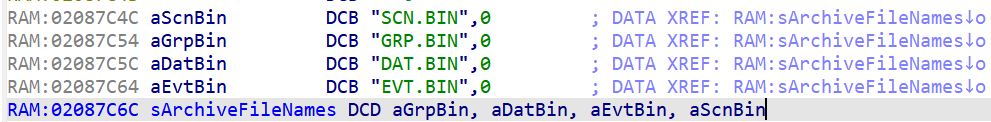

I’ve already gone ahead and marked the value getting loaded into R1 as =sArchiveFileNames – if we pop over to that address in IDA, we can see why:

It’s a list of our four archive names! So that line that says LDR R1,[R1, R10, LSL#2] is going to load the name of the archive in. If we look at R10 in the earlier screenshot, we can see that it’s set to 2. Typically, arrays start from index 0, so that means that index 2 here is going to be aEvtBin – EVT.BIN is the value of %s!

The next line is MOV R2,R9 which is moving the value of R9 (our previous register of interest) into R2. From the text of the error message, we can conclude that R9 stores the file index, i.e. the position of the file we’re loading in the archive! We also know that the value we thought was the number of files in the archive was indeed that. Furthermore, based on the conditions that lead to the error message, we can also conclude that file indices start at 1 and end at the length of the archive (rather than starting at 0 and ending at length - 1 as is more common in computing).

Parsing the Magic Integer

Let’s continue:

RAM:02033D04 loc_2033D04

RAM:02033D04 ADD R2, SP, #8

RAM:02033D08 ADD R3, SP, #4

RAM:02033D0C MOV R0, R10

RAM:02033D10 MOV R1, R9

RAM:02033D14 BL sub_2033A70

We’re calling sub_2033A70 with the following parameters:

- R0: The archive number (2 =

evt.bin) - R1: The archive file index

- R2: An address

- R3: Another address

In other words:

sub_2033A70(2, 0x24C, address1, address2)

Let’s dive into sub_2033A70.

RAM:02033A70 PUSH {R4,LR}

RAM:02033A74 MOV R12, #0x18

RAM:02033A78 MUL R4, R0, R12

RAM:02033A7C LDR R0, =dword_20C19D4

RAM:02033A80 LDR R12, =dword_20C19D0

RAM:02033A84 LDR LR, [R0,R4]

RAM:02033A88 LDR R0, [R12,R4]

RAM:02033A8C LDR LR, [LR,R1,LSL#2]

RAM:02033A90 LDR R1, [R0,#0xC]

RAM:02033A94 LDR R0, [R0,#4]

RAM:02033A98 MOV R1, LR,LSR R1

RAM:02033A9C MUL R0, R1, R0

RAM:02033AA0 STR R0, [R2]

RAM:02033AA4 LDR R0, [R12,R4]

RAM:02033AA8 LDR R1, [R0,#0x10]

RAM:02033AAC LDR R0, [R0,#8]

RAM:02033AB0 AND R1, LR, R1

RAM:02033AB4 MUL R0, R1, R0

RAM:02033AB8 STR R0, [R3]

RAM:02033ABC POP {R4,PC}

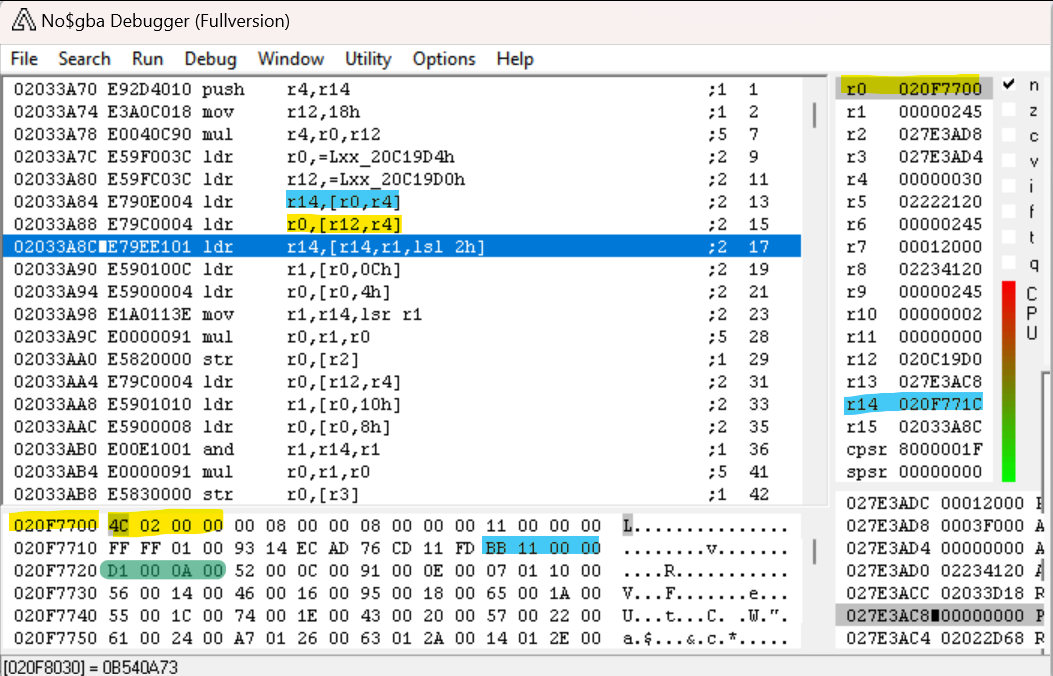

This subroutine isn’t too long, so we should be able to figure out what it’s doing; however, there are a lot of bits where it loads from some memory addresses and I don’t know what’s stored in those addresses. So let’s head back to the debugger.

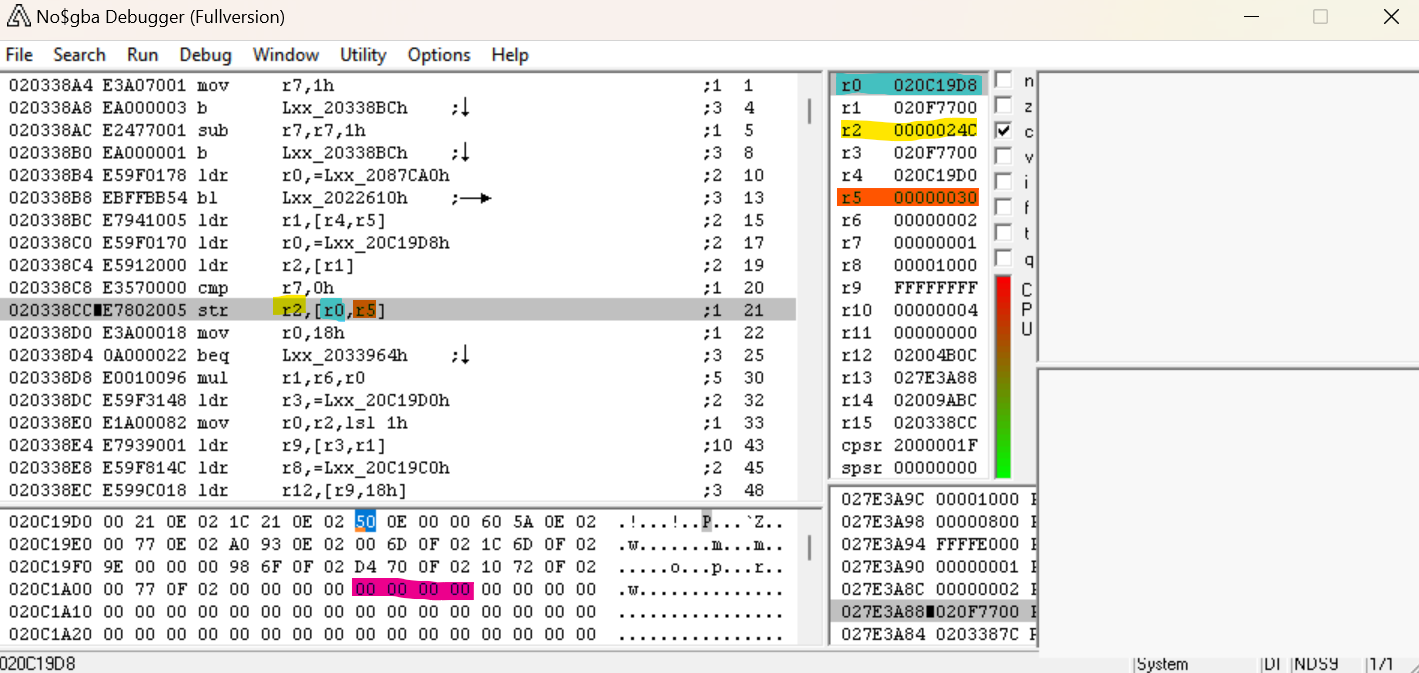

After executing a few steps, we can see that the first part of this subroutine is just loading the address of the evt.bin header we’ve already found into R0. It’s also setting LR (which is called R14 in no$) to the address (highlighted in cyan) right before the first magic integer (highlighted in green). Interesting! The currently highlighted instruction is LDR LR, [LR,R1,LSL#2] – this is going to load the value at the address LR + R1 * 4 into LR. R1, remember, is the file index – therefore, this is loading the magic integer that corresponds to that file index! (Recall that the magic integer array starts at 1 rather than 0, so to make it zero-indexed we need to start from the address directly before the first magic integer.)

In C#, we can represent this as:

public void sub_2033A70(int archiveNumber, int index, uint address1, uint address2, byte[] archiveBytes)

{

int numFiles = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Take(4).ToArray());

uint magicInteger = BitConverter.ToUInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x1C + index * 4).Take(4).ToArray());

}

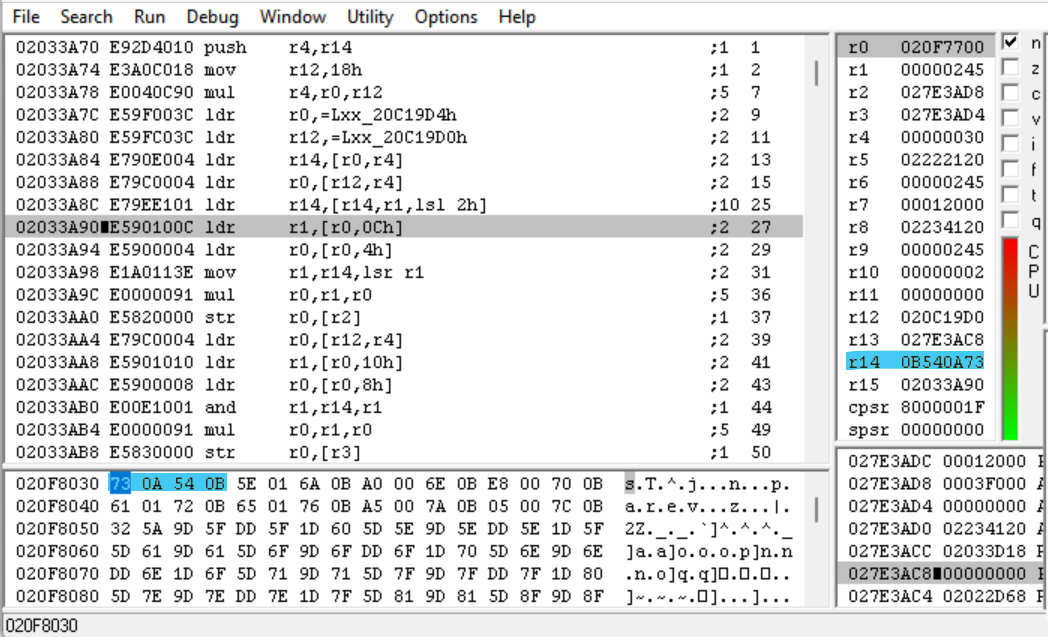

The address we should be loading from is 0x020F771C + 0x245 * 4 = 0x20F8030, and indeed, when we step forward we see that value loaded in. Now that the magic integer is loaded in, let’s see what happens next.

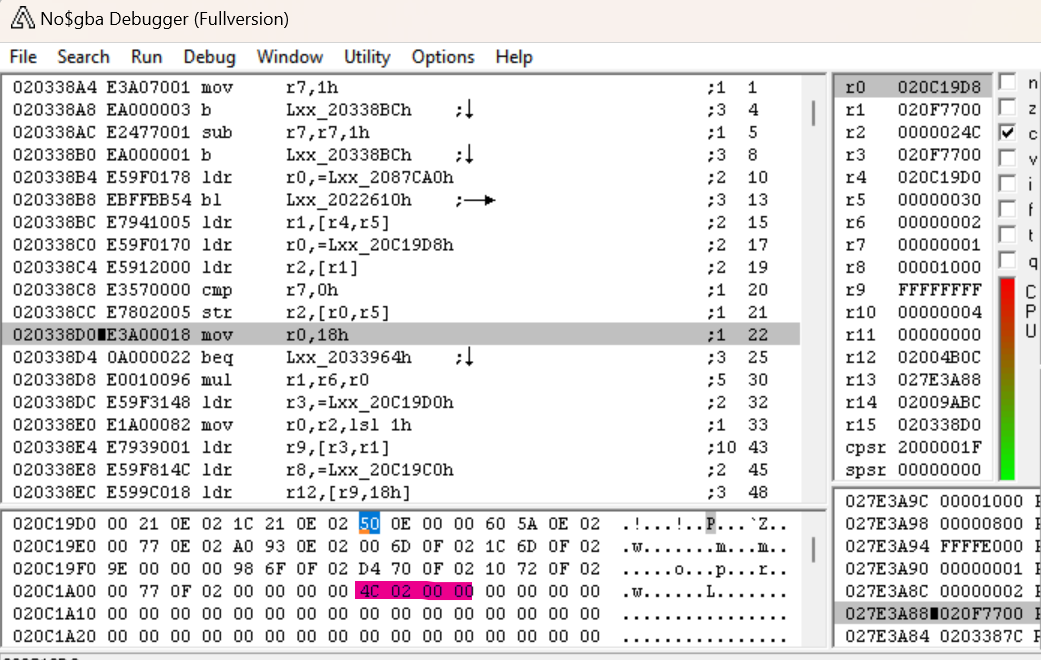

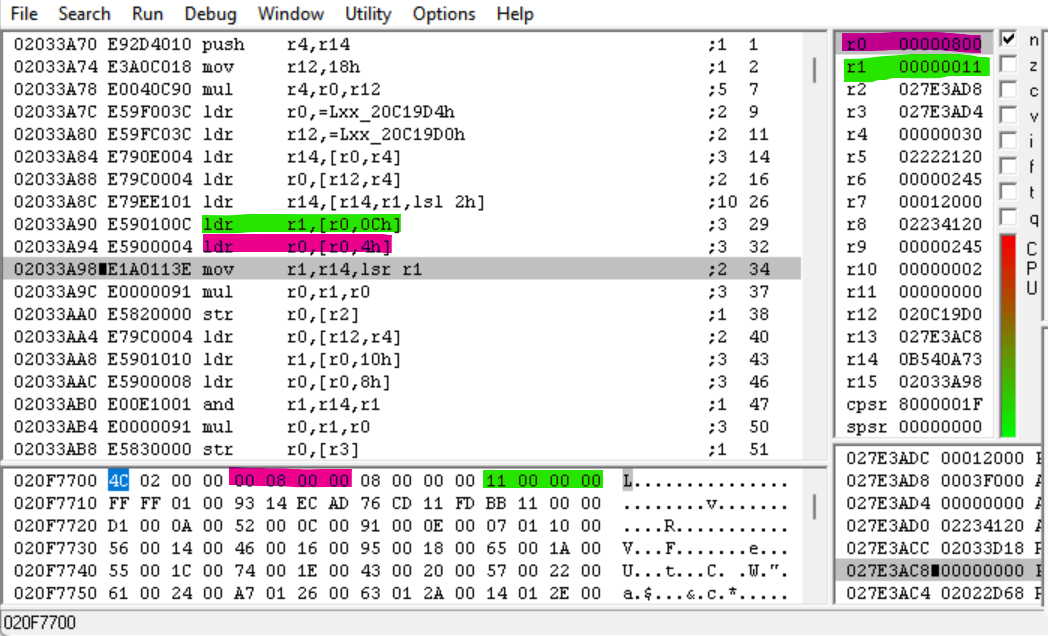

The next two instructions load the integers at offsets 0x0C (green) and 0x04 (pink) in evt.bin into R1 and R0, respectively. These instructions are then used in some calculations:

MOV R1, LR,LSR R1– This instruction shifts the magic integer right by the value of R1 (0x11 or 17) and stores the result in R1. Since magic integers are 32-bit integers, this gives us the 15 most-significant bits of the magic integer.MUL R0, R1, R0– This instruction multiplies R1 by R0 (0x800) and stores the result in R0.

Continuing our C# translation, we have:

public void sub_2033A70(int archiveNumber, int index, uint address1, uint address2, byte[] archiveBytes)

{

int numFiles = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Take(4).ToArray());

uint magicInteger = BitConverter.ToUInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x1C + index * 4).Take(4).ToArray());

int msbShift = BitConverter.ToUInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x0C).Take(4).ToArray());

int msbMultiplier = BitConverter.ToUInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x04).Take(4).ToArray());

uint value1 = (magicInteger >> msbShift) * msbMultiplier;

}

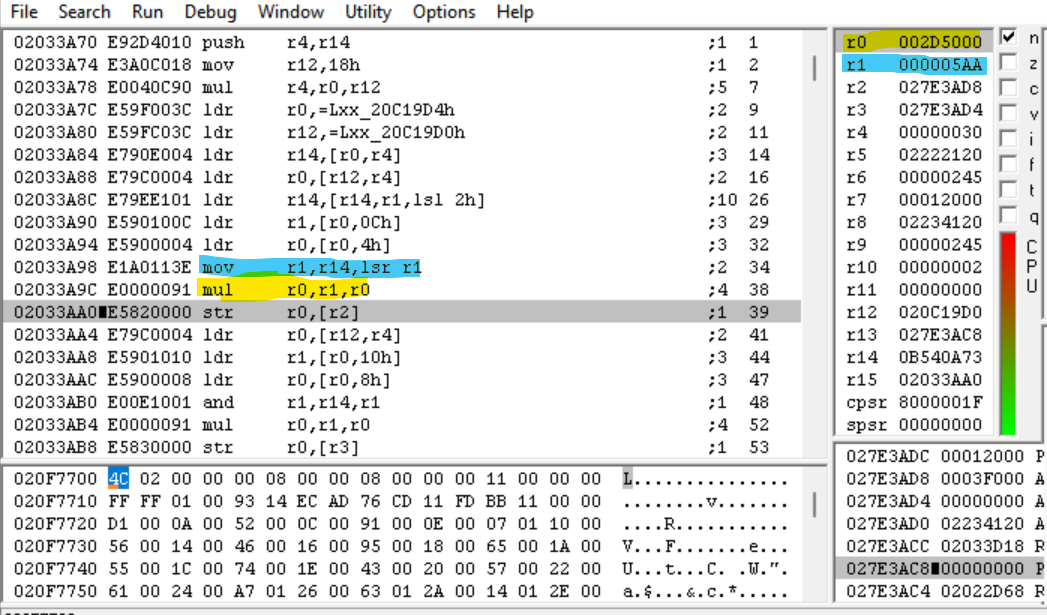

After executing these two instructions…

The value of R0 is now 0x2D5000. Wait a second – we just multiplied the top part of the magic integer (the one we saw consistently increasing!) by 0x800 (which every offset is divisible by). Could we have just calculated a file offset?

We did indeed! We just found the routine for calculating the offset of a file given its index! But the magic integer is still loaded into LR, so we’re not done with it yet.

The next instruction stores our freshly-calculated offset in memory. The instruction after that loads the starting address of the evt.bin header again. After that, we have two instructions that are similar to what we saw before.

This time, we’re loading the values at offsets 0x10 and 0x08 into R1 and R0, respectively. Once again, we’re going to use these values to do some math on the magic integer.

AND R1, LR, R1– this instruction is performing a bitwise-and between the contents of R1 (0x1FFFF) and the magic integer. This effectively gets the 17 least-significant bits of the magic integer (the complement to the 15 most-significant bits we calculated above).MUL R0, R1, R0– this instruction multiplies R1 by R0 (0x08) and stores the result in R0.

In C#:

public void sub_2033A70(int archiveNumber, int index, uint address1, uint address2, byte[] archiveBytes)

{

int numFiles = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Take(4).ToArray());

uint magicInteger = BitConverter.ToUInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x1C + index * 4).Take(4).ToArray());

int msbShift = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x0C).Take(4).ToArray());

int msbMultiplier = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x04).Take(4).ToArray());

uint offset = (uint)((magicInteger >> msbShift) * msbMultiplier);

int lsbBitwiseAnd = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x10).Take(4).ToArray());

int lsbMultiplier = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x08).Take(4).ToArray());

uint value2 = (uint)((magicInteger & lsbBitwiseAnd) * lsbMultiplier);

}

The end-result of this calculation is 0x5398.

And that’s the end of the function. So we’ve found the offset, but what’s that 0x5398 number? Let’s head back to the caller function in IDA and see if we can figure it out.

RAM:02033D04 ADD R2, SP, #0x30+var_28

RAM:02033D08 ADD R3, SP, #0x30+var_2C

RAM:02033D0C MOV R0, R10

RAM:02033D10 MOV R1, R9

RAM:02033D14 BL arc_processMagicInteger

RAM:02033D18 MOV R0, #0x18

RAM:02033D1C MUL R1, R10, R0

RAM:02033D20 LDR R0, =dword_20C19D0

RAM:02033D24 LDR R6, [SP,#0x30+var_2C]

RAM:02033D28 LDR R0, [R0,R1]

RAM:02033D2C LDR R5, [R0,#4]

RAM:02033D30 ADD R0, R6, R5

RAM:02033D34 MOV R1, R5

RAM:02033D38 SUB R0, R0, #1

RAM:02033D3C BL sub_201D310

RAM:02033D40 MUL R4, R5, R0

RAM:02033D44 ADD R0, R6, #0xFF

RAM:02033D48 ADD R1, R0, #0x300

RAM:02033D4C MOV R0, R1,ASR#9

RAM:02033D50 ADD R0, R1, R0,LSR#22

RAM:02033D54 MOV R0, R0,ASR#10

RAM:02033D58 STR R0, [SP,#0x30+var_30]

RAM:02033D5C LDR R1, =sArchiveFileNames

RAM:02033D60 LDR R0, =aReadSIdxDOfs0x ; "read:[%s],idx=%d,ofs=0x%x,sz=%dKB"

RAM:02033D64 LDR R1, [R1,R10,LSL#2]

RAM:02033D68 LDR R3, [SP,#0x30+var_28]

RAM:02033D6C MOV R2, R9

RAM:02033D70 BL dbg_print20228DC

Note the debug string five lines from the bottom ("read:[%s],idx=%d,ofs=0x%x,sz=%dKB"). After the magic integer is processed, we have a debug string explicitly referencing the file index, offset, and size. However, 0x5398 is not the length of this file (we know its offset, so we can check its length manually; including padding, the file is 0x5800 bytes in length). So let’s have a look at the one subroutine call in between arc_processMagicInteger and that debug string: sub_201D310.

The Unhinged File Length Routine

Beware, this one’s a long one. Don’t worry about understanding all of it, it’s not really important for the purposes of this article. It’s an extremely obfuscated way of determining file length.

RAM:0201D310 CMP R1, #0

RAM:0201D314 BXEQ LR

RAM:0201D318 CMP R0, R1

RAM:0201D31C MOVCC R1, R0

RAM:0201D320 MOVCC R0, #0

RAM:0201D324 BXCC LR

RAM:0201D328 MOV R2, #0x1C

RAM:0201D32C MOV R3, R0,LSR#4

RAM:0201D330 CMP R1, R3,LSR#12

RAM:0201D334 SUBLE R2, R2, #0x10

RAM:0201D338 MOVLE R3, R3,LSR#16

RAM:0201D33C CMP R1, R3,LSR#4

RAM:0201D340 SUBLE R2, R2, #8

RAM:0201D344 MOVLE R3, R3,LSR#8

RAM:0201D348 CMP R1, R3

RAM:0201D34C SUBLE R2, R2, #4

RAM:0201D350 MOVLE R3, R3,LSR#4

RAM:0201D354 MOV R0, R0,LSL R2

RAM:0201D358 RSB R1, R1, #0

RAM:0201D35C ADDS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D360 ADD R2, R2, R2,LSL#1

RAM:0201D364 ADD PC, PC, R2,LSL#2

RAM:0201D368 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

RAM:0201D368 NOP

RAM:0201D36C

RAM:0201D36C loc_201D36C

RAM:0201D36C ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D370 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D374 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D378 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D37C SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D380 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D384 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D388 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D38C ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D390 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D394 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D398 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D39C ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3A0 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3A4 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3A8 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3AC SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3B0 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3B4 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3B8 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3BC ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3C0 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3C4 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3C8 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3CC ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3D0 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3D4 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3D8 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3DC SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3E0 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3E4 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3E8 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3EC ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3F0 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D3F4 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D3F8 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D3FC ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D400 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D404 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D408 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D40C SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D410 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D414 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D418 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D41C ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D420 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D424 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D428 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D42C ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D430 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D434 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D438 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D43C SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D440 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D444 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D448 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D44C ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D450 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D454 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D458 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D45C ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D460 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D464 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D468 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D46C SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D470 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D474 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D478 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D47C ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D480 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D484 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D488 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D48C ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D490 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D494 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D498 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D49C SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D4A0 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D4A4 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D4A8 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D4AC ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D4B0 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D4B4 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D4B8 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D4BC ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D4C0 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D4C4 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D4C8 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D4CC SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D4D0 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D4D4 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D4D8 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D4DC ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D4E0 ADCS R3, R1, R3,LSL#1

RAM:0201D4E4 SUBCC R3, R3, R1

RAM:0201D4E8 ADCS R0, R0, R0

RAM:0201D4EC MOV R1, R3

RAM:0201D4F0 BX LR

Here it is in all its glory: what I have dubbed the “unhinged file length routine.” That 0x5398 number was indeed not the actual compressed length, but rather an encoded compressed length that was decoded by this routine. A quick FAQ:

- Q: Why is there so much repetition in this routine?

A: This is the result of a function of some compilers (including ARM compilers) called loop unrolling. Basically, there is a tradeoff made in favor of execution time over program space when the compiler can statically determine how many loops will occur at compile time. - Q: What does that mean?

A: Don’t worry, it doesn’t really matter. Point is, that’s a loop, so we can treat it as a loop. - Q: I’m seeing a lot of

ADCSandSUBCCinstructions here. What’s up with those?

A:ADCSis “add with carry, set flags.” Essentially, this means that we add two numbers and, if the previous operation resulted in a “carry,” we add one to the sum. We then set or clear the carry flag depending on whether that addition resulted in a carry. A “carry” here refers to “unsigned overflow” – when a 32-bit integer exceeds its maximum value and loops back around.SUBCCis “sub if carry clear.” This means we subtract two numbers if the previous operation did not result in a carry. - Q: Why would the devs do it this way?

A: They want to fuck with me specifically.

Out of the Woods

Whew! That was a lot of assembly. We could keep going down through subroutines, but we’ve accomplished our main task now: we understand a lot about how Shade bin archives work. If we return to our original list of what we expected an archive might have:

- We found the number of files (it’s the first four bytes of the archive).

- While there don’t seem to be obviously-located filenames, we did find the mapping between a file’s index (which appears to be how it’s looked up), its offset, and its compressed length

- The file data is definitely present and padded to be 0x800-byte aligned.

Nice! That’s great progress. Let’s see if we can write something to parse the archive now.

Writing Our Own Parser

Let’s start by thinking about how we want to represent our archive file in C#. There are four different archives, each with their own file type – to me, this screams like a time for a generic class. To begin, we’ll make a generic class to represent files in the archives.

public partial class FileInArchive

{

public uint MagicInteger { get; set; }

public int Index { get; set; }

public int Offset { get; set; }

public List<byte> Data { get; set; }

public byte[] CompressedData { get; set; }

public bool Edited { get; set; } = false;

public FileInArchive()

{

}

}

Pretty basic stuff – we have properties for the magic integer, the index, the offset, and the compressed/uncompressed data. We also have an Edited property to indicate if we’ve modified the file or not. Finally, we have a blank constructor for now – we’ll let derived classes implement that.

Now to make the generic archive file:

public class ArchiveFile<T>

where T : FileInArchive, new()

{

public const int FirstMagicIntegerOffset = 0x20;

public string FileName { get; set; } // e.g. evt.bin

public int NumFiles { get; set; }

public int MagicIntegerMsbMultiplier { get; set; }

public int MagicIntegerLsbMultiplier { get; set; }

public int MagicIntegerLsbAnd { get; set; }

public int MagicIntegerMsbShift { get; set; }

public List<uint> MagicIntegers { get; set; } = new();

public List<T> Files { get; set; } = new();

}

All of this is stuff we’ve seen before. Now, to the constructor.

public ArchiveFile(byte[] archiveBytes)

{

NumFiles = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Take(4).ToArray());

MagicIntegerMsbMultiplier = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x04).Take(4).ToArray());

MagicIntegerLsbMultiplier = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x08).Take(4).ToArray());

MagicIntegerLsbAnd = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x10).Take(4).ToArray());

MagicIntegerMsbShift = BitConverter.ToInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(0x0C).Take(4).ToArray());

for (int i = FirstMagicIntegerOffset; i < (NumFiles * 4) + 0x20; i += 4)

{

MagicIntegers.Add(BitConverter.ToUInt32(archiveBytes.Skip(i).Take(4).ToArray()));

}

Here, we’re just extracting the values we found from the header and then looping through and extracting all the magic integers.

Before we get to adding files to the archive, we have to convert that compressed length function. I could go through and explain how I converted from the assembly step-by-step, but that would be a lengthy and tedious explanation. So instead, here’s the final code:

public int GetFileLength(uint magicInteger)

{

// absolutely unhinged routine

int magicLengthInt = 0x7FF + (int)((magicInteger & (uint)MagicIntegerLsbAnd) * (uint)MagicIntegerLsbMultiplier);

int standardLengthIncrement = 0x800;

if (magicLengthInt < standardLengthIncrement)

{

magicLengthInt = 0;

}

else

{

int magicLengthIntLeftShift = 0x1C;

uint salt = (uint)magicLengthInt >> 0x04;

if (standardLengthIncrement <= salt >> 0x0C)

{

magicLengthIntLeftShift -= 0x10;

salt >>= 0x10;

}

if (standardLengthIncrement <= salt >> 0x04)

{

magicLengthIntLeftShift -= 0x08;

salt >>= 0x08;

}

if (standardLengthIncrement <= salt)

{

magicLengthIntLeftShift -= 0x04;

salt >>= 0x04;

}

magicLengthInt = (int)((uint)magicLengthInt << magicLengthIntLeftShift);

standardLengthIncrement = 0 - standardLengthIncrement;

bool carryFlag = Helpers.AddWillCauseCarry(magicLengthInt, magicLengthInt);

magicLengthInt *= 2;

int pcIncrement = magicLengthIntLeftShift * 12;

for (; pcIncrement <= 0x174; pcIncrement += 0x0C)

{

// ADCS

bool nextCarryFlag = Helpers.AddWillCauseCarry(standardLengthIncrement, (int)(salt << 1) + (carryFlag ? 1 : 0));

salt = (uint)standardLengthIncrement + (salt << 1) + (uint)(carryFlag ? 1 : 0);

carryFlag = nextCarryFlag;

// SUBCC

if (!carryFlag)

{

salt -= (uint)standardLengthIncrement;

}

// ADCS

nextCarryFlag = Helpers.AddWillCauseCarry(magicLengthInt, magicLengthInt + (carryFlag ? 1 : 0));

magicLengthInt = (magicLengthInt * 2) + (carryFlag ? 1 : 0);

carryFlag = nextCarryFlag;

}

}

return magicLengthInt * 0x800;

}

Now we have a function that can determine the compressed length of a file from its magic integer. But here’s the problem – when we save the file, we’ll have to reverse that and go from the compressed length back to the magic integer. How do we accomplish that?

Well, at some point, someone had a program that could do that, but I am not that person. What’s more, this function is way over my head and I have no idea how to even begin trying to reverse it. But it’s not the end of the line for us – remember that the 0x5398 value is only 17-bits in length. That means that the possible values of the encoded integer (i.e. the input to the unhinged file length routine) range from 0 to 0x1FFFF. That’s only 131,072 possible values which in the scope of things isn’t that many. So we just… calculate all the possible encoded values based on file length and add them to a dictionary. (Since these values are constant, we do this only once in the constructor.)

for (int i = 0; i <= MagicIntegerLsbAnd; i++)

{

int length = GetFileLength((uint)i);

if (!LengthToMagicIntegerMap.ContainsKey(length))

{

LengthToMagicIntegerMap.Add(length, i);

}

}

Then when we want a new magic integer, we just do:

public uint GetNewMagicInteger(T file, int compressedLength)

{

uint offsetComponent = (uint)(file.Offset / MagicIntegerMsbMultiplier) << MagicIntegerMsbShift;

int newLength = (compressedLength + 0x7FF) & ~0x7FF; // round to nearest 0x800

int newLengthComponent = LengthToMagicIntegerMap[newLength];

return offsetComponent | (uint)newLengthComponent;

}

Finally, we’re ready to start parsing the files. All we have to do is loop through the magic integers, get the file offset and compressed length from each, and then use those to take the file data and initialize a FileInArchive derivative.

for (int i = 0; i < MagicIntegers.Count; i++)

{

int offset = GetFileOffset(MagicIntegers[i]);

int compressedLength = GetFileLength(MagicIntegers[i]);

byte[] fileBytes = archiveBytes.Skip(offset).Take(compressedLength).ToArray();

if (fileBytes.Length > 0)

{

T file = new();

try

{

file = FileManager<T>.FromCompressedData(fileBytes, offset); // Don’t worry about this function, all it’s doing is initializing the file.

}

catch (IndexOutOfRangeException)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Failed to parse file at 0x{i:X8} due to index out of range exception (most likely during decompression)");

}

file.Offset = offset;

file.MagicInteger = MagicIntegers[i];

file.Index = i + 1;

file.Length = compressedLength;

file.CompressedData = fileBytes.ToArray();

Files.Add(file);

}

}

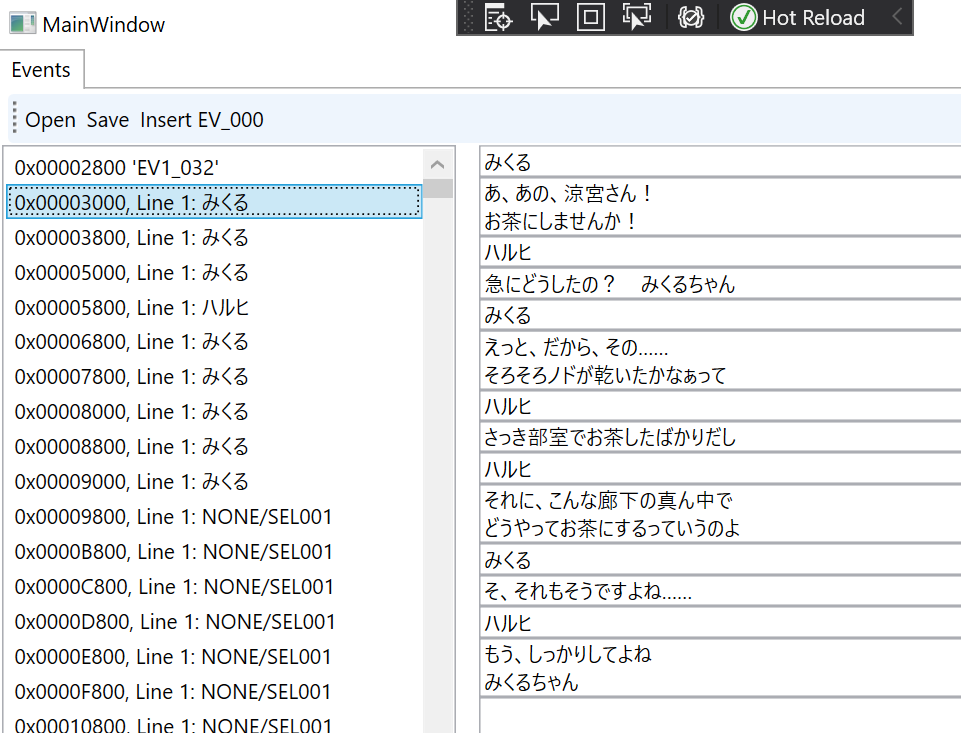

So we have a functional parser now. We can write up a quick GUI to show us how file loading will look and…

Very nice looking! (The text on the right is a preview of what’s to come – I was working on parsing the event/script files at the same time as I was working on parsing the archives, but we won’t be covering event file reverse-engineering in this post.) So now we can open evt.bin and even edit the files inside it. There’s still one step left, though – we have to be able to save the bin archives once we’re done editing them.

Saving the Archive

The ideal way to save the archive is to reconstruct it from scratch, but because there’s data in the header we don’t understand fully we’ll have to settle for editing the header in place. So, we’ll start by just adding the whole header we took while parsing.

public byte[] GetBytes()

{

List<byte> bytes = new();

bytes.AddRange(Header);

Next, we’re going to loop through all the files and add them to the archive in order. If the file hasn’t been edited, then we’ll just add it directly to the archive. If the file has been edited, though, we’ll have to compress the edited data.

for (int i = 0; i < Files.Count; i++)

{

byte[] compressedBytes;

if (!Files[i].Edited || Files[i].Data is null || Files[i].Data.Count == 0)

{

compressedBytes = Files[i].CompressedData;

}

else

{

compressedBytes = Helpers.CompressData(Files[i].GetBytes());

}

bytes.AddRange(compressedBytes);

Here, we hit a snag – in some cases, the edited file is going to be longer than the original file, right? This will happen more often than we think since my implementation of the compression algorithm is noticeably less efficient than the implementation the developers used, so even files that stay the same size decompressed will end up longer on recompression. The solution to this problem is actually pretty simple, just a bit tedious: we move everything further down.

Why is moving things down tedious? Well it comes back to the magic integers – those contain offsets for each file. By moving the file down, we’re changing its offset, which means the magic integer will change as well. So we need to write code to do that.

if (i < Files.Count - 1) // If we aren’t on the last file

{

int pointerShift = 0; // Assume we’re not going to be shifting offsets at all

while (bytes.Count % 0x10 != 0) // ensure our file is 16-byte aligned

{

bytes.Add(0);

}

// If the current size of the archive we’ve constructed so far is greater than

// the next file’s offset, that means we need to adjust the next file’s offset

if (bytes.Count > Files[i + 1].Offset)

{

// Calculate how much we need to shift the magic integer by

pointerShift = ((bytes.Count - Files[i + 1].Offset) / MagicIntegerMsbMultiplier) + 1;

}

if (pointerShift > 0)

{

// Calculate the new magic integer factoring in pointer shift

Files[i + 1].Offset = ((Files[i + 1].Offset / MagicIntegerMsbMultiplier) + pointerShift) * MagicIntegerMsbMultiplier;

int magicIntegerOffset = FirstMagicIntegerOffset + (i + 1) * 4;

uint newMagicInteger = GetNewMagicInteger(Files[i + 1], Files[i + 1].Length);

Files[i + 1].MagicInteger = newMagicInteger;

MagicIntegers[i + 1] = newMagicInteger;

bytes.RemoveRange(magicIntegerOffset, 4);

bytes.InsertRange(magicIntegerOffset, BitConverter.GetBytes(Files[i + 1].MagicInteger));

}

// Add file padding

while (bytes.Count < Files[i + 1].Offset)

{

bytes.Add(0);

}

}

Bam. We have working code that will shift the magic integers. So let’s test it – let’s modify a file and save the archive and see if we can change some text.

I present to you the first text I ever edited into the game. 🥰

If you’re interested in seeing the end-result of the archive code, you can check out the code on GitHub!

What’s Next

We’ve now parsed and repacked the archive successfully. The next thing we’ll talk about is the first files I reverse-engineered: the event files, which contained the script for the game. But before that, I’ll be posting an addendum to these two posts which will contain answers to commonly-asked questions and a few historical notes on the actual process we underwent to get this all working. Thanks for reading and please look forward to it!